Sue Press, president of the

Ole and Nu Style Fellas Social Aid and Pleasure Club

at her house

in Treme

Sue: Social aid and pleasure clubs, what we do is, we parade once a year. We have 52 clubs in New Orleans. We have clubs downtown, which is my part of town, and we have clubs uptown. Uptown does their thing, downtown does their thing.

|

Sue: And we have a ball every year. Sometimes you want to step above and feel like you belong with the elites, so we give this ball that’s strictly formal. But we kinda bend when it comes to men, you can have a tux and a tie, or a suit and a tie. Ladies have to have full length gowns on. It is a must, or you won't get in. It is beautiful, we have a full court, the king, the queen, the dukes, the maids, and it’s beautiful. You have to see it. Also, we present Debutantes with our ball. My sister can afford to present a Debutante with the Zulus, but it is kind of expensive to be a Debutante with Zulu. And then I had another sister, who had a daughter that was an outstanding young lady, and she couldn't afford her daughter’s debut. So I thought about it and said, “we have a ball every year, let her debut with us.” And that’s how we get the response from Debutantes in our parade. Outstanding young ladies, who are doing really well; we give them a sense of pride, to keep on striving, just keep striving. We want to be there to give them that little push.

(See pictures of Sue's 2016 annual ball here.) |

Sue with her mother, Ms. Emelda

Sue: When we started the organization I wanted to get older guys with younger guys and to mentor them, in a good way, meaning that we teach them things and show them things. So we teach them about why the club is important and how we put it together. We teach them why we do this, why we second line, what that part of the culture is about, where it comes from. And we also encourage the children to give back, with the book sack drives, feeding the elderly, and so forth. We have the children heavily involved so that they do everything that we do. Everything we do is based on the children to show them that you have to give back. With the second line club we do raise money sometimes because not all parents can afford to come up with the money. For the ball, young children come because it makes them feel good about themselves, to put on a suit and a little tie, and they say, “Thank you! Thank you Ms. Sue!” And they just get so excited. It gives them a sense that it’s not just about a pair of jeans and a t-shirt. Life has more to look at. It is broader than what we see in our surroundings. And we do things with them, take them places, even if it is no more than taking them to the park, get them in the yard and put on a barbeque, just to show them some sense of family orientated activity. Children want to be heard, they want to be listened to, not just told something. And I can sit down with them for hours and they can go at it. They can ask me whatever. And sometimes they may have a little friction between them. And then I’ll listen to them, and tell them, “let’s think of something positive, let’s think of something better.” Try to show them, everybody has a view, everybody has an opinion. We’re all different and we’re never gonna always see things the same, so there has be to a point where we can compromise, because we need to work together. I even make them ask their mom for $5, $10, because I also want them to give something, like when we do something for the elderly, I expected them to buy a pack of socks, just so they can also bring something, so they feel good, like they're actually part of the community. |

A house in the neighborhood.

Sue and her mother with fans and decorations from their 2016 second line parade.

Sue: When I say decorations, this is what we make by hand, this is actually made by hand. My son made this; he is very talented. Our theme last year was cameras, so he made all these different kinds of cameras. This is a camera that's made out of cardboard that my sons each detailed. And this is a belt that goes around my waist. And we decorate our whole outfits. It’s clothes and your shoes and your decorations. It's a part of our culture. It's an art that we do; handmade art, it takes time, it's time-consuming. You want it to be perfect. This is what the men wear around them. I don’t wear anything over my chest, because I'm a woman. And I'm the only woman in the club, it's 10 men. They wear yokes around their necks. All of this is made from cardboard and things like that. Oh that’s another part of our decoration. We hold this one in our hand, it’s called a fan. My mother also rides with me—

Ms. Emelda: The mother of the club

Sue: That she is. She makes her umbrella and she dresses up. And every year she's on a horse and buggy. She leads our parade. She's the mother and we’re the wind beneath her wings. And she’s gorgeous every year. And that’s a part of our culture, that's part of what we do. This will be our 19th year, April 3rd. Twenty years will be next year. The clubs are very family oriented, most everybody in there is family, a couple close friends, but 98% of the club is made up of family members; brothers, sons, and nephews. We mastermind this together. We don’t really tell. It’s this unsaid thing. Our club says, “It’s a secret you have to wait for, till you get there and see me.” We don’t really tell what we are coming out with the next year or the year coming up. And it's what most clubs do, it’s like an unsaid thing, a competition. But a good competition. Everybody wants to come on the street and see, “What did you create?” You know, you're making all this by hand, so they want to see. We are one of the few clubs that actually does our own. A lot of clubs get other people to do it. But we do every bit of it ourselves. We don’t send anything out to get done. |

Sue at her club's 20th annual second-line parade, 2018

Sue: This is one of the cameras. This is one of the 10 that we made. They were all different. All shaped differently. My son builds that all with his hands. He did the building, his sister did the trimming, another brother does the stick in there to hold it tight, and another one lays the material down on it. It’s a process. It looks like this, but it comes from many, many pieces. This looks simple, but it's like three pieces of material, about 20 pieces of trim. It takes time! This takes a lot of time! It's really tedious and time-consuming. And that’s a part of our culture and part of our life, and part of our family. We look forward to it. I get all excited and nervous and whooping and hollering. At the parade, most people are enjoying the day, eating breakfast, but the day of our parade we're actually working here until….somebody said one time, “It's 12:51 and they only have 5 minutes to make it!” But we’re gonna make it; we don't sleep and we work it. And that's us. That's what we do. And we enjoy doing it. |

At her club's 2018 parade

Sue's son, Askia, at her club's 2018 parade

At her 2018 parade

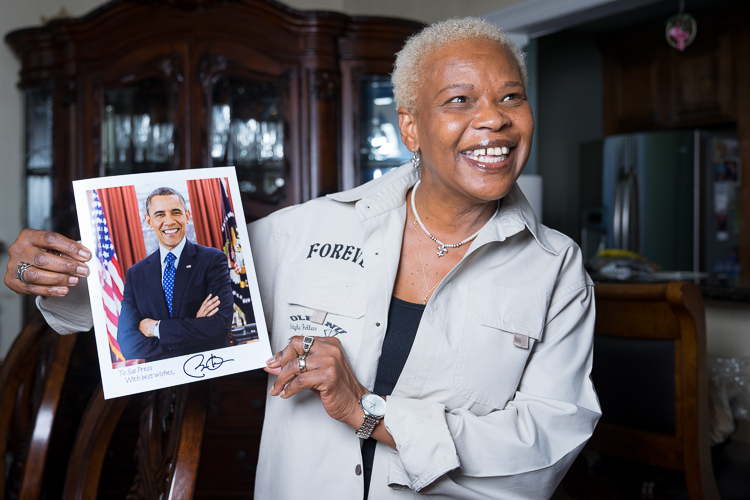

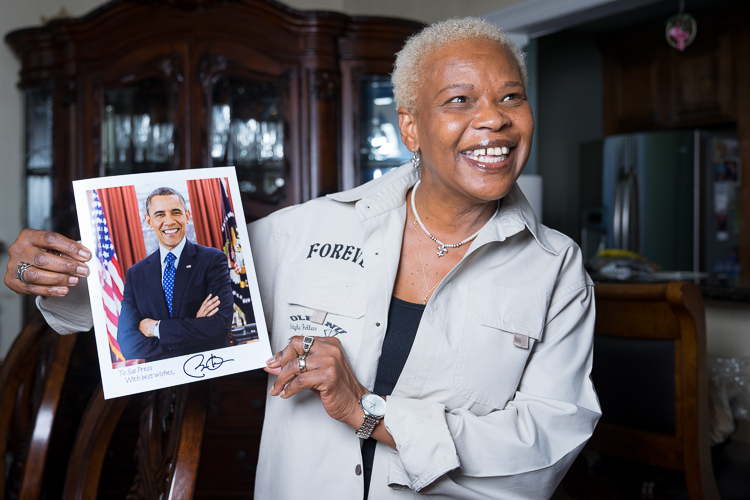

President Obama signed a portrait to Sue

Sue: We do a lot of things yearly. We put on book sack drives for children in the community. We try to assist parents in the community that are striving….give them a little helping hand. And back to the community, number one, our community. I came from twelve. My Mama had twelve children. And I’m sitting down one day thinking, “somebody had to help this woman. Somebody had to help her.” And I remember people worked in the cafeteria, we lived across the street from the school, and they would hand pans of food out the windows to my mom. This is a true story, my mom used to win a raffle at each store, you know, where you put your name on the back of a receipt during Thanksgiving and Christmas. And every Thanksgiving she would win from all the stores. We used to get excited! My Mama would always get drawn and we came to realize that she had the most children in the neighborhood, that’s why we were always winning. When I got to the age, as a large family, I thought, we need to give back. We need to give back to our community. Somebody had to help my mom—twelve children! I want to be more than just a second line club. I wanted to get the community involved. I wanted us to be more involved with the community and with the children within our community. So, that’s how we started with the book sack drive. We went from giving away 50 book sacks to giving away 300 some-odd book sacks. Not only book sacks, we also give away school supplies. We started giving away 50 coats, and now we give away 300 coats every year. We work a lot with elderly people. This year we adopted the center my mom goes to. And we gave them pajamas, nightgowns, dusters, slippers, and so forth. We wrapped each individual one and put their name on them. It was over 60-some elderly people that we helped. And that was amazing! Just to see the joy on their faces. That's what we do. That’s what this family does. I’ve been in this community for many, many years. I have a 38-year-old son and a 25-year-old son and if you do the math that's how long I have been in the neighborhood [laughs].

Ms. Emelda: ...And her 84-year-old mother.

Sue: …And my 84-year-old mother. She'll be 85 on the 25th of next month and I don't know what we’re gonna be doing, because it’s gonna be Mardi Gras there will be so much confusion going on. |

Sue and her son, Tyrone, prepare a lunch for a parade stop

for another social aid and pleasure club

Sue: This is a part of our culture, clubs give each other stops. A stop is when you give them some refreshments, drinks, sandwiches, chicken, things like that. You serve them. They put you at a stop in a particular area. It could be around a club, say a lounge. We stand there on the side and give the people in the parade a stop, because a parade lasts four hours, so you get thirsty. Different clubs are at different stops. Some clubs have four stops, or maybe eight stops, with different people waiting on them to come through their neighborhood. That’s mainly what a stop is, where you’re greeting and serving another club when they put on a parade. And you have some where they are dressed up in their outfits and they all meet the next club and bring them to their stop. So our club is going out there. And that’s it. Once you're finished serving them you pack it all up and follow the parade, or do whatever. So we’re the second stop today. |

The second line parade that day

| Sue: I do a block by block cleanup. I just have all these visions and try to get them out. What I did, was I put out some flyers to let everyone know we’re doing a block by block cleanup. But I had two electric scooters that a young lady donated to me, and I told them, we’re going to do a little drawing, and pull them after we have a little hamburger barbecue. They were excited, cleaning up. Just to give them the sense that this is our neighborhood and we should not have anyone else coming to our neighborhood to clean up our neighborhood. We want a sense of pride, we want our neighborhood to be clean. And it worked out pretty good. I tried to get something going, where we take a blighted property and clean it and make it like a court-yard, and set it up for the children. The children would be responsible for keeping it up, keeping it tidy. So, they are not gonna want anybody coming into their neighborhood to clean if for them. This will give them a sense of, “this is my neighborhood and I want my neighborhood to be clean, too.” |

Sue at her home in Treme

Sue's neighbor, Gwen

Gwen: I've been here a long time, in fact, the next block where the bridge is, my grandmother owned a house and the city forced them to sell for the interstate, which I heard they are going to take down right there. This is my parent’s house. I bought this house from them at least 20 years ago. I raised my two kids in this house. Let me go back, my brothers and sisters; there were 13 of us. This was my parents third house they bought. They bought the house because we lived in the lower ninth Ward. 1965 is the year I graduated from high school. Betsy came and washed us out. So my mother was afraid of water, so my father bought this house. Years later they bought another house and I was able to buy this house from my parents.

This is supposed to be Treme, so I can’t do anything to the front of my house. All the designs and all the artwork. Our neighborhood is quiet, believe it or not. With all the violence, we've been blessed not to have a lot of violence around here. It is changed a lot. But the lot over there used to be a grocery store, when I was growing up, I'll be 70 in July. Across from the grocery store there was another place that sold seafood, so it has changed a lot from when I was growing up. But it's looking better. I've just never had any problems, because my girls are 47 and 49 now. And they went to school around here. And Sue and I we all get along like family around here. And I go to church on Ursuline Street, St. James on Ursuline. It's coming back, you know, it's been a struggle since Katrina, but it's coming back. I love my neighborhood.

|

Sue with her neighbors, Chris and Gwen

Gwen: I see the neighborhood building back up as a family neighborhood like it used to be. When the grocery was there we supported the grocery. I don't know if they’re going to do anything down the street where my grandmother's house was, but it kind of upset me that they just kind of forced them to sell it. They didn't have a choice and they just gave them what they wanted. And they built that interstate and now I hear talk about tearing it down. It makes no sense. But I see us as being family oriented. I call Sue my sister, and she has a large family, sisters and brothers. And like I said, I'm one of 13, so you know I see positive things coming back like it used to be a long time ago.

I love my neighborhood. Like I said, we’re family around here. And that's what it's about. We have to look out for each other. I have some new neighbors here, I don't know their names. They’re young. I think they have a wine store something, maybe on Magazine Street. They’re a young couple. Bought the house and remodeled. That's family. Like I said, we just live as neighbors, but I can remember when I was younger, blacks didn't really live on Dumaine, most of this was white. This was some years ago. In fact, the man that owned the store was white. Ms. Teresa and them was white. They had a lot of Caucasians. And you know with integration how they start moving out? Guess what, they coming back now. The value of the property is up around here. I can remember some things. Like I said, everybody's family, doesn't matter what color; treat people like you want be treated and look out for each other. That's what I live by. I believe in God and I'm my brother’s keeper. |

Sue's neighbor, Claudette

Claudette: I've been here for years. Back in the 80s, watching new neighbors come in and watching the neighborhood grow, for positive reasons. And we live in the heart of Mardi Gras, so we really enjoy our community, and we would do whatever we to make it better. It is just a wonderful neighborhood to live in. We don't have too much stuff going on that’s out of order. We’re enjoying our life here.

Q: how have you found the recovery since Katrina?

Claudette: Successful? Not quite. You know, some people are still having problems, some people are still trying to come back, and it's kind of hard for some people. But they here and they’re in their homes and that's the most important thing.

|

Q: So most people who lived here been able to come back okay?

Claudette: Somewhat. I was a first responder. I stood here; I had to work at the Superdome, helping people leave to get out the city, sheltering people in the Superdome, keeping them safe and everything. So I did a lot of that, and rescuing people as well. I was with the civil Sheriff at that time. So we had to stay; there is a lot of stuff we had to do. I was the first to come back in my neighborhood, so they were able turn my lights on for me; once they drained the meters and got the water out of the gas lines; we were able to get our lights on to protect the neighborhood. I watched a lot of people's homes to make sure nobody broke in.

I see a big change, a great change [more recently]. A lot of people are redoing their homes and everything is looking up. So I’m happy with that. And I have good neighbors, so that's the most important thing. You look out for each other and make sure everything is safe. |

When they built the Interstate highway down the middle of North Claiborne Avenue in the 1960s,

they cut down the beautiful live oak trees, like those you still see lining St. Charles Avenue,

and displaced many minority-owned businesses along the avenue.

Community members have painted oak trees on the outer columns to commemorate this loss,

and they have painted local heroes and landmarks on the inner columns,

like this one that Sue is standing next to,

showing famed gospel singer, Mahalia Jackson.

There are a number of vacant lots in Treme, and sometimes art projects appear in them.

Residents disagree, whether they like these projects or not.

Some newer residents have sought to convert vacant lots to urban gardens or farms.

Corey: I don't live here. I live close. But I've been gardening here for five years or so. We are rebuilding this little herb garden right here. I'm one of the few people growing here and I just happen to be here right now doing some cleaning and stuff. We're kind of in a revitalization phase, I had a knee surgery about a year ago and a bunch of our growers are dealing with health stuff right now, so we're kinda getting the space back in order. But we're working on getting a youth program back up going. I used to have a business that prioritized hiring formerly incarcerated people, folks from the neighborhood. It also has an alternative funding model. And also having community plots and places for folks to just be growing food. We're all really into aesthetics; gardening in weird shapes. Y'all should feel free to walk around if you want to. |

Sue: This used to be a corner store. I don’t know what it is now. It’s like you buy candles and all that kind of thing. It’s not traditional for our neighborhood; you don’t see anybody I know in there. Not us; we go to St. Jude’s & buy our candles. |

This looks more like a traditional corner store, though Sue says it is new.

Pat, manager of the Candlelight Lounge, one of the last remaining old-style barrooms in Treme,

where local jazz musicians play. Many jazz musicians lived in the neighborhood, but toured the world.

Sue: When I grew up, there was a barroom on every corner. We call them barrooms. A lot of people would call them pubs and lounges and all that, we call the barrooms. And after Katrina, we didn't know better, the city started flooding with the people from elsewhere. They didn’t want the local barrooms in their neighborhood because they said, “there’s a lot of bad things that can happen” and so forth. |

Pat, with Terry, who is Sue's cousin, in front of the Candlelight Lounge.

Pat: Oh I've been here since 1974. I have been in the 6th Ward for years and I'm still around the corner.

Terry: I was born in ‘58.

Pat: And he was born 58, he been here!

Terry: Long time ago. I was born right around the corner and that's my cousin Sue. That’s my cousin right there!

Pat: This is Tuba Fats Square. [The owner will] be back on the Saturday before Mardi Gras. He live there [points across the street]. He bought it and I take care this property. John Richardson, he's the one who made the property for us to have it. He'll be here the Saturday before Mardi Gras.

Q: It’s looking beautiful

Pat: I keep it up every day!

Q: It didn't always look beautiful

Pat: No, no it didn't. |

While we were at the Candlelight, Glen Andrews of the Grammy-winning Rebirth Brass Band

stopped by. Glen is from the neighborhood and is an old friend of Sue's.

He played a jazz verse of Bye Bye Blackbird.

Second Line Grand Marshal, Oswald “Bo Monkey” Jones in Tuba Fats Square,

next to the Candlelight Lounge. Anthony "Tuba Fats" Lacen was one of the important jazz musicians.

Sue: This is Bo Monkey. He's the grand marshal, and everybody in the city knows he’s a grand marshal, especially for a funeral or anything like that. He’s very famous in our city. He's been to Spain, Europe, all around the world. It’s like the bands, he’s traveled with the bands, and they’ve been everywhere. Places I only dream of they’ve been.

Bo: My name is Oswald Jones, born and raised here. I've been here, like 70 years. I was raised a block and a half from here. My dad was a great musician by the name of Jesse Jones, and my brother Benny Jones also the Treme brass band. I march with them, I’m the grand marshal of the Treme brass band. Also my son is a musician, Corey Henry.

Q: And so your granddaughter is Jazz?

Bo: Jazz is my granddaughter. I'm the grand Marshal of the band, been around through funeral marches. I’ve marched with different brass bands and I was a young man coming up. So many other bands. Been part of the history of this country. I’ve been here, there, through weddings, funeral marches.

Of the older people, they have stopped that [participating with the brass bands], and they gave me a reward, City Hall gave me an honor for that, they gave me a plaque for that. I appreciate them. And I’m going to try to keep doing the same thing, try to teach the youngsters how to do the same thing. Keeping the tradition alive.

To be for real with the club we called the 6th Ward High-Steppers. We started from here. I was like 17 years old, and we made it happen, so every year around Christmas time we have a Christmas color we wear: red and white. That was our colors. And we’re given a beautiful job of that. You may have seen us on TV, nationwide. We’ve been around the world, and I've enjoyed everything. It's a part of my natural history. And I ain’t given up yet, it's still going on. I want to thank you all and I appreciate y’all.

I enjoy myself on Tuba Fat lot. You can find me out here every day. He was a good friend of mine. Very good friend. |

One of the merchants that survived on Claiborne Avenue was the Charbonnet Funeral Home.

Funeral homes have a special relationship with jazz music and social aid and pleasure clubs.

SAPCs began in the 19th century or earlier as mutual aid societies and pooled money to bury their dead,

and they always hired a brass band. Around the turn of the last century, these organizations

invented a new kind of music in Treme, which was called Jazz, and hence, the jazz funeral.

Charbonnet still sponsors rest stops in the clubs' parades.

Sue: This is Charbonnet, a family-owned business. And they've buried just about everybody who’s lived here, gone from here, and come back here. They have about nine locations now, all over, all for us. |

Sue "knocking" on a friend's door ... by calling through the mail slot.

The former barroom, the Caledonia (like the song), just down the street from the Candlelight Lounge.

| Sue: Right here used to be a barroom too. That used to be a local store. This used to be a bar, the Caledonia [sings] “don't treat me so bad,” this is the famous Caledonia. |

Another former barroom, a little further down the street from the Candlelight & Caledonia,

Ruth's Cozy Corner, which went out of business after a shooting in the year before Hurricane Katrina,

and had remained vacant. Now, restauranteur

Fatma Aydin, who came to New Orleans

from Turkey in the 1980s, is opening a Turkish cafe and bakery in the former barroom.

It is being renovated and will be called Fatma's Cozy Corner.

Sue: And this was where Ruth’s Cozy Corner was. This was where from my mama’s time to my time, we used to have some fun. This was one of the famous barrooms of our neighborhood right here. It's a shame this whole block has all changed now. But that orange house they're still holding onto it. The mom just died. The husband is still living. The one next to it was some friends of ours. They lost it bailing their son out of jail. The one next to it was a doctor, and the one next to it was a man named Mr. Candy but they took all of that. Now they’re worth $600,000, $800,000. This one right here was $250,000. They bought it for little or nothing. |

Paul, who has lived in Treme since shortly after Katrina, lives next door to Ruth's Cozy Corner.

He says there are only about three home owners still living on the block.

The rest of the houses are becoming short-term rentals like Airbnbs.

Paul: Well the neighborhood has changed pretty rapidly. Well right now, Alvin, myself and Richard over there, and this pair of people here, and the people living in the far yellow house down at the end are the only people remaining here. All the rest of these are single house short-term rentals. Airbnb. This one, that one, the one next to it, and so on. There isn't much of the neighborhood left. In three or four years it's pretty much been destroyed, I would say. On the next block it's the same story. I don't know if the city Council expected that's what was going to happen or not. When they allow the whole-house rentals they basically destroy the neighborhoods.

Q: That's shocking.

Paul: It is. It's more shocking than Katrina. Katrina left more than this. One thing it's doing is it's making people want to buy these, you see on the next block there are four houses that were really infested and now these two here are being worked on, and I saw a real estate agent looking at those two tall ones, I suppose those will get worked on, but probably for short-term rentals.

Paul: Every time I sit on my stoop somebody comes by. I have a hard time keeping enough books in it. [referring to his "Treme Branch Free Library"].

|

Many residents are unhappy about the Airbnbs that are popping up all over the neighborhood.

Treme is right next to the French Quarter and is becoming very popular with tourists

as an "authentic" place to stay, rather than a big hotel.

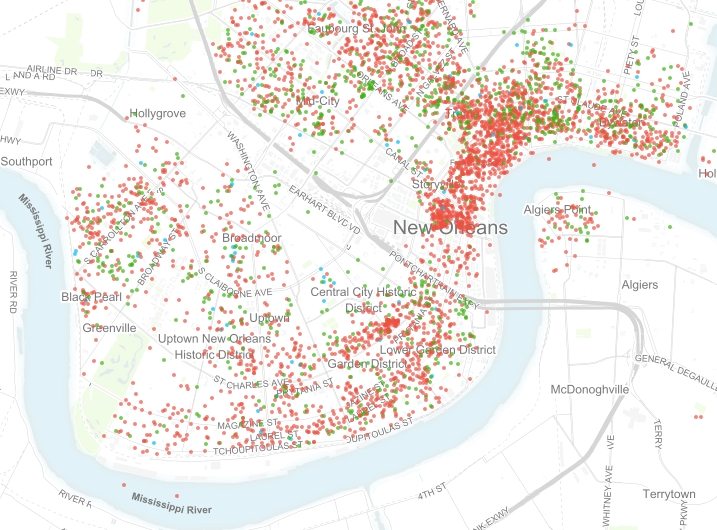

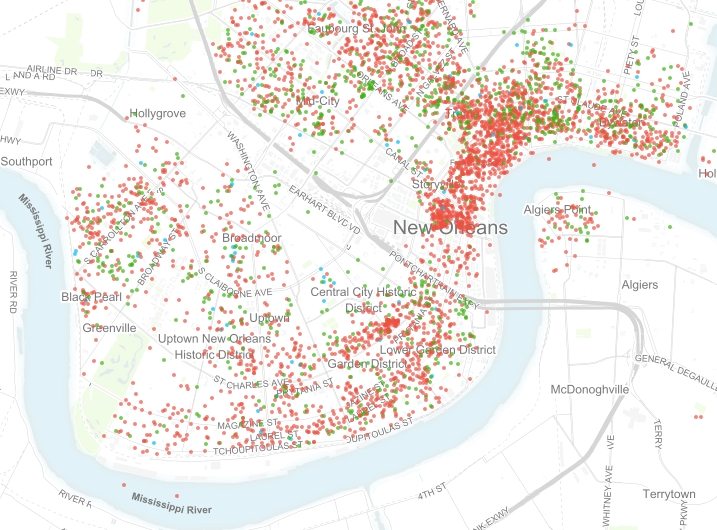

Airbnb listings as of October 3, 2016, according to Inside Airbnb.

New Orleans has perhaps the highest density of Airbnb's per capita of any city in the world,

and

Treme has some of the densest listings in the city.

Redeveloped Airbnb short-term rental houses. This one is said to have sold for $400,000.

Redeveloped Airbnb short-term rental houses. This one is said to have sold for $600,000.

Another Airbnb short-term rental house.

Sue's friend, Lucille, who has lived in Treme all her life.

Sue used to live across the street from her, and they have been friends since childhood.

Lucille: My brother is a Zulu witch doctor [in the Zulu Social Aid and Pleasure Club], so I'm going to give you this coconut. Tutu’s—that's my signature. I made 400 coconuts! We’re riding in the parade, we’re on his float. I'm only giving it to little girls and little boys; the little girls are getting coconuts with the tutu and the little boys are getting the coconut with the Mohawk. |

Lucille: My name is Lucille Deborah McWilliams. Make note of the “Mc” Williams because that's very important, that means I have Irish heritage and that is the reason that my family is in the Tremé. The way it goes, my great-grandfather when he came over from Ireland with his brothers, making their way to Morgan City, they stopped in New Orleans and he fell in love with this beautiful woman he thought was Irish, just like him. Only thing was, she was mulatto, having one black parent, but she looked just like him. He wanted to marry her. He married her, and they told them that he will be better staying in the Tremé. So he stayed and we stayed in this area, so I'm born, bred, and will be buried from the Tremé. The Tremé people, the dedicated Tremé people, tell you the three B's: we’re born here, bred here, and then Charbonnet will bury us here. The three B's: born, bred, and buried. And my family, they like to call me their little Irish potato because I'm browner than the rest all my brothers and sisters. Well, my grandmother and grandfather had seven boys and all of them look like they were passé-blanc—pass for white—you can't, you couldn't tell my dad and his brothers from the average Caucasian; they all had red hair, green eyes, very fair, last name McWilliams. Out of all the grandchildren, there were 29 of us, but with their little experiment - they decided to marry very dark complected women - I'm the only dark grandchild. My brothers, my sisters, and my cousins are all red hair, green eyes, and light complexion. The funniest thing, my children: red hair, green eyes, light complexion. So, I’m the little Irish potato of the family. |

Lucille: Now, let me tell you about this French Quarter here! Do know why the Tremé exists outside the French Quarter? The real reason? Not for segregation. I'm gonna tell you the real reason the Tremé exists and that's why so many blacks in this area. Okay, when it was just the French Quarter, their wives were so genteel they couldn't deal with the yellow fever, they can’t deal with this, couldn’t deal with that, so they would lose their babies. But their husbands would set up a Plaçage with the quadroon. So the dividing line was Rampart Street. He'd come over to this side and live with his quadroon and her children. He’d cross over on that side and go back. And never the two should meet. There would be people standing at Rampart telling the Caucasian women, “why do you want to come in the Tremé? Are you trying to see your husband's kids?” So, when people talk about, “oh the Tremé is right outside of French Quarter.” When you grow up [in the Tremé] you know there’s a different story. That's why the houses are big; they wanted their children to be accustomed to the same type of life that they couldn't give them. That's how the Ursuline nuns on St. Augustine got started. They wouldn’t let Henriette Delille and them go to Cabrini, so her dad brought over nuns and brought them to St. Augustine. He still was going to see that his children, through his Plaçage, was going to be well educated. That's what they did. So, when they talk about this and that—see when you come here you find out the true story. |

Tourists on Segways in Treme. The tour leader dive-bombed us, almost hitting us.

Lucille: One day I saw them [a Segway tour] I had to walk over and say, “excuse me, are you talking about the Treme? Maybe? Because you are not talking about the Tremé. I don't know what that is that you’re telling, but it's not my story and I know; I've been here 59 years.” Like I said, born, bred, buried. I done lived on every corner. When the bridge took the funeral home we moved on Ursuline. When we moved from Ursuline, we moved back on St. Phillips, which is the Tuba Fat Garden, and then from the Tuba Fat Gardens, we rooted here. In the Tremé, because it’s such a sense of family, you don't venture outside of Tremé. We don't need to go to the suburbs.

Sue: We don't need to go to Lakeview.

Lucille: We got beautiful camaraderie where we’re living.

Sue: That’s what you call family. Like I was saying, we lived right there [points across the street]. The cafeteria ladies at the Craig school would send their pans of food through the windows. Sneaking it to my Mama. Families fed families.

Lucille: Right.

Sue: People fed people in this community. My Mama had a store on every corner. She would always win when you put your name on the back of the receipt. And all the times she would win all the groceries, and we’d be like, “huh?” We’d be happy. And as you got older, you realized—she had the most children. You know, we thought, “Boy we’re lucky!” “We’re winning all that!”

Lucille: Because they [the stores] wanted to leave you with your sense of dignity. So, when they talk about this and that—see when you come here you find out the true story. When they're on the scooters riding around they make up a story, but if you want to know the true stories then you ask us! But we don't sell our story. Now if it’s to learn and educate, then I’ll be happy to. But you learn, your story is “told but never sold.” We could write books if we wanted to. |

Lucille: Gentrification. This is the oldest black neighborhood in the United States. And since Katrina, it allowed them to have gentrification. Now, let me clear this up for you, there were always a mixture of cultures, there were always Caucasians that lived along Esplanade Ridge because those kids went to John McDonogh on Esplanade of the Tremé. There were always the Italians, they called them Dagos, because we always had the stores Joe Ciacci and Ferrara and stuff like that. So, we always was a mixed neighborhood that got along well, did everything together. But now, since Katrina it is gentrification. The oldest established African American neighborhood in the United States—you’ll be able to count the black families on your hand. And the reason that's happening is because a lot of them had family homes, but the family member may have died, and in order for them to come and keep the home, the ones that sold to—mainly to Caucasians—and let me tell you what they're doing, I make no apologies, when you want to teach you want the truth, when they come in, like they buy that house for little or nothing, they fix it up and they sell it for $600,000. |

Lucille: Squatter’s rights. That's a beautiful porch right here, this green one, right where you can see the piece of the green. That's what happened. They got it through squatter’s rights; they just moved in. Took it. That's it, it is theirs now. And the thing about it is that they're not they're not buying it to benefit the neighborhood. They want to do these Airbnbs. We’re losing our sense of community, neighborhood. And then they want to have ordinances to stop the music. You’re in the birthplace of jazz, but they don't want the music. They don't want second lining. If I die on a Wednesday and my people not gonna bury me until Saturday, every night until I'm put in the ground they're going to second line through this neighborhood. They don't care how late, but they don't want it. They’re big houses. So yes, we’re going through gentrification of the Tremé. When they came in, I want to call them like carpetbaggers, you had some families that was down on their luck, and FEMA was giving them a hard time, and this and that, they came in with pennies to make to make millions. But they don't want to live here. Airbnbs. Like she said, most family homes were just that: the older people might've had the paperwork, but the next people didn’t, the next people, the next people. So they come, “oh you don’t have papers.” I'll tell you that green house that down there. Squatter’s rights. That lady went to New York with her son, took sick, passed on. Everybody was waiting for everybody to come back, and next thing you know, we see these people living there, and we’re like, “well, who are they?” After checking: Squatter’s rights, because nobody came back. I had never heard of such. Never heard of such. |

Lucille: The detriment of Tremé started when they tore down the houses to make the bridge. I used to live, I was born next-door to the funeral home, and then all of those houses up until the funeral home, because the Charbonnet‘s would not sell their property, they did the I-10 highway. And now they’re talking about taking the I-10 down. The Tremé was so self-sufficient that we were envied. We had our Orleans, and Basin was our own Canal Street. We had our own stores. Our own supermarkets. We had our own clothing stores, shoes, everything. We did not have to go to them for anything. So our money we made it and we spent it here in our neighborhood. This neighborhood was to die for. This was a black neighborhood, well a mixed neighborhood, but predominantly black. When they ran that highway, they destroyed that part of our town, they took those businesses. So now they want to remove that, put the businesses back, put the trees back, well that's what I grew up with. Why did you take it down? The street car that’s running up and down Rampart, we grew up on that streetcar, but you buried it. And now because you're coming back into the area, oh now you want the ambience of the streetcar. Well, we had that, but you didn't want it when it was a black neighborhood. But now you want the ambience of the streetcar.

Lucille’s sister: Y’all giving the real history? [laughter] Y’all better get the Tremé right! |

This is Sue's brother's house, a few blocks away.

Sue: See that house right there? They don’t have the money to fix it. They’re trying to hold on to it; they’re trying. |

Renovations under way

Margaret, director of the Treme Market Branch performance space, with her husband and daughter

Margaret: You are standing in a historic location; this is Treme Market Branch. Treme Market Branch was first opened in 1925. There was a smaller bank on this location that faced St. Anne Street. In 1935 because of a boom in the Treme neighborhood, a financial boom, the smaller bank was torn down in this bigger bank erected, so it opened in 1934. It first it opened as The Bank of Germania, because this area was predominantly German. The neighborhood changed; it became more African American, more Haitian, more African—people of color—and the bank also changed, it was bought by CCB which is Canal-Commercial Bank and Trust, who later became First NBC. So the bank bears the name Treme Market Branch because it was one of eight branches and CCB. I'm going to point you to a picture outside on one of the columns, of the actual Treme Market. |

Margaret: So, the Treme Market was one of 24 or 34 open air markets that were operated by the city of New Orleans. The last one standing was the French Market in the Quarters, but many of the neighborhoods had open markets that sold fruits and vegetables, and mercantile, and shoes, and whatever else. So, because that market, which was located Caddy-corner on the street over, was doing such great business there and the neighborhood was booming, that's why this bank became the bigger bank it that it is. It operated until 1956, that's when the banks decided to bring all the smaller branches back to central locations. This magnificent building became a shoe repair store: horseshoes, cow shoes, people shoes. It operated until about the mid-60s when the freeway when up. So that monstrosity there cut the neighborhood in half. It really became a problem. There was 113 African American owned businesses along Claiborne Avenue, when the when the freeway when up and Oak trees were torn down, all those businesses shut down and many of them did not return. This building was opened again in the late 70s for a shoe repair store, it kind of flailed a little bit, closed down in the early 80s, and was vacant and closed for about 32 years, until we bought it and renovated it. It's now a theater. We do live music, we do plays, live performances; it's a live performance theater and also a venue or rental event space. |

Margaret: This whole back area was rebuilt. Right in the middle where that gold bar is, above that was just a room and it had a 20 ton air-conditioning unit. It took two weeks to get it cut up and pulled out. It's as big as the whole gold band and it went all the way back to the wall. When we finally got it out we discovered that there'd been another arch, so this building, like I was telling you, it was built above standards in the 30s so all the arches are symmetrical. There’s eight of them here. The Windows—I think—set the tone. There's three more there, one above our head here, and we discovered the eighth one, which was deteriorated, back there. |

Margaret: This bank, at the time, was built with more advanced standards. There's newspaper articles that talk about how you can read a newspaper at 5 PM from just the lighting outside because of the windows. As you can see, the 21 foot ceiling is not supported by any columns, there’s steel beams that run through the roof, so it really was built state-of-the-art for 1935. |

Margaret: Our company is Treme Market Branch LLC, and the building name is Treme Market Branch, we left it. We’re space to put on things—live events. We love when people from the neighborhoods, or from New Orleans, approach us. We had a play here in the middle of December, a local playwright wrote it and we performed for two days. We are beginning our jazz series again. We do an international dinner series. The biggest band we've had here might've been a quartet of four-piece ensemble; the piano moves, and we the xylophone player that also played the piano, they kind of bounced back and forth. We’re very happy and pleased. The building has turned out really nice. |

The painting on this column under I-10 commemorates the historic Treme Market.

There used to be open-air markets all over New Orleans, but only a few still survive.

The Treme Market also fell victim to the building of the I-10 Interstate highway over Claiborne Avenue.

Sue's neighbor, Tom

Tom: What do I like about the neighborhood? It's like they help children around here, like if they see you doing something bad they tell you what’s good. It's quiet around here; no badness around here. We got helpful people around here. They got a boxing coach, he boxes with me; teaches me boxing, teaches me football, he exercises with me. And they got a police officer—he keeps the neighborhood safe. Got a soccer player, he’ll do some soccer with me from time to time.

Q: Do you go on the parades with Sue?

Tom: Uh huh. Yeah, it's fun. |

Sue's husband, Darryl