New Orleans

Neighborhood Portraits

Cut Off, West Bank

"..." (from The New Orleans Data Center)

New Orleans

|

The old Rosenwald School, now decommissioned and owned by a church.

The current school, Algiers Technology Academy

![]()

Penny

Dari: This is my great grandparents’ house. No one lives there now. This is a very old house, it’s a family house. A lot of generations went through there, in terms of my grandparents and their children. But it’s now owned by multiple siblings, so no one occupies the house. We’re trying to decide if we want to build it back up. |

![]()

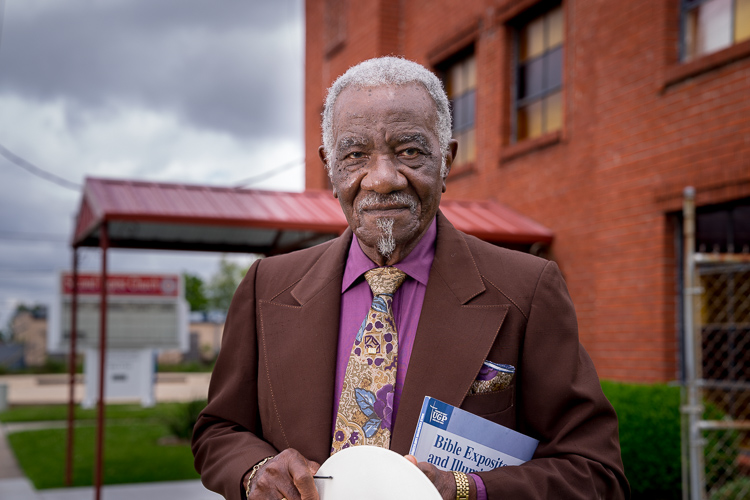

Outside the Second Baptist Church of Cut Off, founded in 1868

Isiah Riley, Deacon: This neighborhood is very unique. It's, you know, always everything in this community, always was owned and operated by blacks. You know, we had our own school. We broke the ground in governing the building of the school. We had our own church, we had our own grocery store. Everything down here. We didn’t know what it meant to rent something—everybody had their own property. We have our own Cemetery, you name it. I say that because most places in the black community, whites had owned everything, the grocery store and everything, but not here. So, we was very independent people. Very much independent because, we didn't know what it was to, when you had to go through the side door. When blacks were not allowed to go in the front door, in my time if you wanted something at one of those places, you had to use the side door and we wasn’t used to that kind of stuff. Everything, we’ve got what we need right here. Very rich community, of which it is inherited: church, school, you name it. Q: Do you feel like the neighborhood has continued along the same lines? Or do you feel it is changing now? Riley: Oh, it done changed a lot. It done changed a lot. You see, everybody had known each other, you know. Now you have…after they started building those homes down on the outsides…see this community was only consisted as five streets. So, when you get Sullen, Boyd, Casimire [streets], or anything like that, that was the Cut Off. But all this other stuff on the side, on the outside, no. We had an opportunity to buy all that ground, but you know, the people never wanted to buy. So the other people bought it and they started building up the with projects and started bringing all kinds of people in, and that's what caused it to change; when different people start moving in, different ideas, different lifestyle, you know, all of that. |

Inside the Second Baptist Church of Cut Off, founded in 1868

Penny: [Describing the portraits on the walls] The man at the top, with the bowtie on, that's Rev. Reason Boyd. He took over the church in 1954. The pastor before and was Edmond Jones and he's the one who formed the church. He saw need for a church, so in 1868 after slavery he decided to build a church for the community. So, he built the church from 1868 to 1904, pastor Edmond Jones. Then Edmond Jones died in 1904. Then after Edmond Jones died in 1904, Rev. Reason Boyd took over. So, when Rev. Reason Boyd took over in 1904, to 1954, well, during the time of his pastorship he became blind. So even though he became blind he was still able to preach. This was my pastor, right here with the bowtie, Rev. Earl Green. He took over, this is the adopted son of pastor Reason Boyd, but he still kept his birth name Green. So he was pastor from 1957, I think, to 1994. Then he passed away. And then this is his grandson, Rev. Tyler Green. So, was like a family passed on through generation for the church. And then pastor Green, he just died in 2015. He had cancer and he passed away, and then after pastor Green passed away, then Rev. Sigler took over. Q: Only the four pastors so far? Penny: Yeah, over 150 years. From 1868 until present time. |

Rev. Andre Sigler: I’m fairly new here. I'm on my second year. |

Alvin Rose, Deacon: Our grandfather built part of the church too. This was the old church over here [pointing towards a side room]. They built this part here in 1957 [indicating the church sanctuary] and if you can look on the corner stone of the building you can see, from when they started, the board and everything else, and the pastor at that time was Rev. Reason Boyd. They tore the old church down and added this one in 1957, and in 1968 we added this building here. And one thing about this community, they all pretty much own their own home. And we have three different, what they call a “society” that help out, where the people came together and help out each other in that area. So, a lot of our ancestors and them, pretty much in this church we’re all related. We still have that mentality of saying, “it's a society.” We have a tradition here in this community that we take care of one another. Q: What is a society? Rose: So, a society is a bunch of people that come together, put their money together, have their own doctors, and like for some family members they get sick, and we have one person that carries the book for that person because they have a list of everyone that is on there. And they have a meeting once a month. Everyone comes and pays their little two dollar dues and stuff like that, but it’s taking care of their health when they have to go to the doctor, and sometimes bury them. So, we had three different societies. A lot of us was in all of them. My parents, like all of our parents, paid for each one of the children if anything happened to them, sick or death. The community, with the money they put in, would be able to bury them or help them with healthcare, stuff like that. Q: Is it the same as a social aid and pleasure club? Or is it different? Rose: No, it's not a pleasure club! It's not like no Zulu or nothing like that. This is only strictly for help. If the family need something people go to that society. That’s how people got a chance to own their own homes or things like that. You have some of the leaders that can go talk to them and get the loan and things like that. So, once people were taught to go in and do it, pretty much everyone in the Cut Off had their own home. |

Penny and Dari (PhD)

Penny: And also, what brings us together as a community is when we have death in the family. The community comes together as a whole. So, the good thing I love about living here in the Cut Off, everybody is one. They put away their differences. They come together: they bring food, they bring money, they bring cars, they just love on each other. So that’s what makes this community so rich, and so historical, because you get a phone call saying somebody passed once or somebody’s sick, they picking up the phone, they put away their differences. Like Alvin says, and Mr. Riley says, it's a historic community and everybody just comes together. And it was instilled in us through our ancestors, through our grandfather, grandmother way back when Edmond Jones built this church. And he instilled in them, then Rev. Boyd instilled in their congregation, on and on up to Rev. Green and the late Rev. Tyler Green. So that's instilled in us today and we’re trying to pass it on to our kids, which now is a new generation. So, they're always say, “no that's the old way!” But no, old ways can’t change. Because we got to continue to keep this love and show them what our community was like way back in that time. Alvin Rose: [pointing at Dari] She told you, she's been a member here since a very young age. And one of the things that, the church has sponsored her. And she could probably tell you what they did for her, and not only just for her, for other young people in the community that we do it. We’re about to have like a 20th year anniversary for our scholarship, that we get our recipient, our young people that graduated, we give them funds. And a lot of them have done well, like she is right now. We have a lot of them that moved away due to Hurricane Katrina, but we’re trying to get them back, to come for this function here. |

The old church bell

Charles Mills, Deacon: I got a chance to ring the bell a few years ago, when Brother Leroy was out. Because up until a few years ago, we would ring it every morning after the press service, and I was so proud because I was carrying on the community’s tradition. Mills: This community has a very rich tradition in that this church was founded like three years after slavery ended, which meant the people who built this church, not the structure but build the institution, were former slaves. And I think we even have on record that some of them could write, so we have records of what they did. So, this whole community is rich in that it has survived not just Hurricane Katrina, but it survived Jim Crow, it survived everything, and it’s still here. And it's probably only as strong as many of the Black communities in the country, but that is some strength. In particular it’s spiritual strength. And the thing about this community, this church is like a foundational part of this community. So, all of the Black communities exist around this country, particularly in the South, they exist because of their spiritual strength. So, when we do Black history programs here in the church, we do it based on people from the church. So, we make sure the kids know who their founders were. Dari: He's my mentor! Mills: Right! And I moved here! I'm not from here originally. But I’m from a town that is similar to this. And so I’m able to fit in. So, her family [pointing to Penny], her family [pointing to Dari], they all, they're people [from here]. I always try to tell them to have pride in the fact that they had a vision, and based on their vision this community is producing all kinds people, you know, craftsman, professionals, whatever, so a lot of time what we see is the depressed side where, you know, people have to resort to drugs and alcohol and that sort of stuff just to cope, but at the same time we’re not just coping we’re actually thriving in many areas, like Dr. Dari here! So, I’m proud to be a part of it. Dari: So, what about the bell? Give us a spiel on the bell. Mills: So, the story I am told is that every morning for church on Sunday, they would tone the Bell. I think ‘tone’ is the right term. And then every time somebody died they would tone the bell, and they had different tones for different events. And so, every Sunday morning at seven o’clock we have press service here. So, I was so honored one time when a more senior Deacon was out of town and he told me, you know, “I want you to tone the bell.” He brought me out and showed me how to do it….and of course I didn't do a right when it was my time! And the people in the community was telling me, “I knew it must have been somebody else because you didn’t do it right!” |

![]()

Penny: This house from the back, it used to be my aunt's sweet shop back, way back in the late 60’s. And then, when Katrina hit they had to tear it down. But I have a picture of it before got torn down, because when I came back from Katrina I started taking pictures of the houses that was damaged for my memory. You know, just to have keepsakes. So, I took a picture of the house before it got torn down and remodeled. So, this is actually used to be a sweet shop, and my aunt stayed upstairs, and the sweet shop was downstairs. Everybody used to go there, play the little jukebox and dance and eat their little candy, cookies. And it was my mom's sister, it was her little sweet shop. It was called Aunt Hazel's, Hazel's Sweet Shop. And it’s where everybody came, and I don’t want to say party, but had a nice time [laughs]. Penny: When my aunt, my great-aunt, it was like a two-story. The top with her house, but the bottom was the sweet shop where everybody used to go, like I said have a nice time, sit at the little stool bar. No alcohol was served there. It just was strictly soda pop, dancing, and just having a nice time. And where that fence was, well it’s torn down, there used to be a hall. Where everybody used to go for society meetings, like Alvin used to talk about. Penny: Do you remember when Alvin was talking about society meetings? OK, do you see where this empty lot at? There used to be a hall. So that was one of the places where people used to go to the society to pay their two dollars or their dollar. When someone gets sick or they need to be buried, but the hall is torn down now, but I do have a picture of it now. Good thing I took a picture of it now before they tore it down, so now it's owned by Second Baptist. When they were saying we try to buy our own stuff to keep it, you know, traditional, so what Second Baptist did was instead of someone else coming to buy it, they bought the property, so now is owned by Second Baptist. That’s why its gated like that. |

Penny: Back in time when I was maybe 17, 15, this used to be a ballroom called Ann's Ballroom. This is another place where we, well not me, like my mom, used to go, but not my mom, my mom had kind of slowed down a little bit, but other people from another generation used to come to Ann's Ballroom. It was nothing ratty, it was just something like a social, people used to come, sit down, have them a nice drink. They used to play the music box and just sit down have a nice time. It wasn’t, nobody fighting, cursing. It was just a nice leisure time where everyone would come after work or during the weekend. And just have a nice time. But then Ann died. The reason it closed down is because Ann passed away. And then once Ann passed away, well her husband already had died, so it just was her. And then when Ann passed away, there was nobody else to take over. So that's why. It's like a strip mall. They sort of made a little strip mall out of it, different stores and stuff, but it never came to pass, so what happened, they went and just boarded it all up, and so it never got completed. I don’t know if they didn't have enough money, or whatever happened to it, it just didn't come to pass. So now it’s just there. |

Penny: All of this right here used to be a store. It used to be Hal’s Store. And this used to be a store too, Mr. Mike. They used to call it Hal’s. So, like I said, they remodeled. They made a strip mall, like this is barbershop, a hair salon, and this is like a little corner store now. But it used to be Hal’s Store, it’s another store where everybody used to come a long time ago. It was a White owner. They used to own it and he took a likeness to the Blacks in the community and so everybody took a likeness to him. |

Benn's Grocery has been locally owned for generations

Penny: One of my friends, we all grew up together, her great-grandfather built this store. He said, from being a slave they wanted their own stuff here and the Cut Off. They wanted everything to be owned and paid out, so, paid in full since 1887 [points to the store]. But after the grandfather died... Dari: Isaac Benn, senior. Penny: After Isaac Benn senior died, Isaac Benn Junior took over. And when he died, his son Kermit, he's no longer here with us, he died in 2013. After he died his son George Benn took over. George is not here and that’s why so they didn't want to spend too much time in his store without him being here. |

![]()

The Lower Algiers Senior Center

Penny: Now across the street, was the senior citizens of lower Algiers, it was organized by my cousin Evelyn Gaston. Somewhere back in the 1980 something, no 1970 something, because my grandmother was living at the time and my great-grandmother was living at the time this community center was done. My cousin Evelyn Gaston, she was the director of the Lower Coast of Algiers, and she wanted something for the old people to do. Sometimes as you get old and old fragile you have nothing to do, so what she did, she formed a community center. So, she named it the Lower Coast of Algiers Senior Citizens. She would take them on trips, they would do arts and crafts, you name it. She would just try to make them feel young and alive, but Evelyn passed away maybe like a year and a half ago, so it's owned by her daughter Melanie. She's the new director of the senior citizens so she wanted to keep going in the memory of her mother. |

Penny: [This is] the center for the elderly, they call it Boyd Manor, after the late Rev. Reason Boyd. Remember the church pictures? So, what they did, they wanted to create a living center for the elderly also. So, they wanted to dedicate it to the late Rev. Reason Boyd because he did so much for the community back in those days. |

![]()

Penny: Remember Alvin we interviewed in the church? The drummer. This is his sister’s house. This house been here forever but it just got remodeled. This is the house of Audrey Rose, the drummer’s sister, Mr. Alvin Rose. She got it remodeled, I think it was brick at one time too and they would up doing a reconstruction of it. And this is it today. |

Penny: And the guy was telling you about it was walking with the black shirt on, this was his mother's house. She also passed away. And this house is been here forever, since we were little. Q: When someone tries to sell their house, does it go ok? Or is it hard to sell? Penny: They really don't sell it if the children don't want it. Q: Because it says for sale. Penny: Nobody is probably going to get it. I don’t think nobody’s going to buy it. Probably sooner or later they’re just going to tear it down. I’m just keeping it real. They just got it up there hoping somebody buy it. |

Penny: Hey Bobby! This is my cousin Bobby Jefferson. He can tell you some stuff about the Cut Off too! Bobby Jefferson: The only thing I can tell you about this place here, God bless this place, I mean, and it was like this…when I was coming up over there, on Sullen, if someone would have told us that we were poor I’d’ve told them, excuse my expression, I’d’ve told them they were a damn liar. I mean, because our people here, I mean God blessed this place to the point where our people actually took their time and took care of us. Until the later years when the youngsters started coming up, that second, third generation, bringing in all the filth and everything. And times changed, then Katrina come and you can see what Katrina left. Some people came back and they were able to rebuild, some people wasn’t fortunate enough—just look at this [points across the street]. Look at this guy’s house. That was one of my best friends. You know, we come up together I done partied in that house and everything, and look at it now. So, Katrina did do its damage. Some of us were just blessed. In this young lady right here, my cousin, we all come up and our parents did the best they can, and you know, you can tell from the product. Look at her! [people laughing] Bobby: This was a blessed place for us. Now? I don't even live in the Cut Off anymore, so I can't speak for the Cut Off, but it's not the Cut Off we used to know. This was… it still is, but— Penny: Tell them how used to come together and how we used to go by Aunt Hazel’s. Bobby: Oh yes indeed! Penny: I was trying to give them an emphasis on aunt Hazel’s sweet shop. Bobby: Oh, that was the place! We wasn’t nothing but kids, but we had good fun and it was clean fun. It was good. I was, I would raise my kids here! [laughs]. You know, I would raise my kids here. And then most of the people like at the church over there, most of that, we come from a family of ministers and first ladies and everything. Most of them, they’ve been church all their life. That's all they know, you know, that’s what we strive on. Just try to hang with what we got. If we can get some young helpers, get some of them riffraffs outta here [laughs], it would even be better. Q: Are you still on the West Bank? Bobby: Yeah, I don’t live in the Cut Off no more, I live in Algiers. And to show you how much I hate what’s going on, and it's not just going on in this area, its areas all around. They having family day in Algiers, and its right down the street from my house. I love Algiers. I came from the Cut Off. We don't know how to go out and have good clean fun like we used to have down in the Cut Off. That park over there where Boyd Manor is, people [used to] get out of school out in the evening, go home, do their chores, do their homework, do whatever they go to do, [then] we heading for the park. And you go out there and you see nothing but kids and grown-ups out there playing football. You don't see none of that no more. All that's gone, so what you see is what you get [laughs]. |

In front of the house he grew up in. He lives in another neighborhood now.

Bobby: My mom died, my dad left when I was seven years old, my mom died when I was ten years old, so my grandmother raised me. My grandmother's oldest son owned this house right here, and we were on the lot in the back. So, it was one big yard, but it was family. |

Penny: See that water tower [next door to the house]? I know you took a picture of that water tower. But you see that water tower? It was our play area. See, we had nowhere to play. We didn't really have anywhere to play except for the greens, like Bobby was saying earlier. And this water tower, so we used to go inside the water tower and play around. We used to go inside. Back in ‘the days’ everything was opened us. Because it wasn’t like it is today. And we used to go inside the water tower, and play around the pole, because to us it was like a little game. And we just sat there, play jacks, play tag, play red light. I mean, nobody ever harmed us, nobody ever said, “oh y'all get away from there!” because we had nothing to play with, so the water tower was another area we used to play in. Penny: All of these empty blocks we passed, they were houses, and they torn it down. And remember I told you about the lady who had the senior citizen center? This was her house, right here. She passed and her husband passed. So, her children didn't want the house, but they kept it for the kids, which kids just let it go, so now they just put a sign up and keep cars there so people won't trespass, you know, break-in and nothing like that. |

Penny: You see this this lot right here? My great-grandmother's house was on this lot. So, they tore it down it because nobody wanted it because it getting so old, so they took it down. Like I was saying, in this neighborhood to preserve their family heritage, so my cousin on my mom’s side, he heard that this lot was for sale, so what he did was he called my brother, because this used to be my grandparents’ home, my dad’s mom and dad, my daddy grew up in this house. So instead of somebody else taking the lot, my brother purchased the lot to keep in the family. And so, what he did, he made little areas for them, like this needs to be like the little Sunday, that’s what I’m saying, there isn’t anyone sitting outside today. We used to sit down, play music, play spades, and put tables and chairs out here. So, it did us good because he bought the lot to keep in the family. Dood Johnson III: This is my grandfather's house. He passed on and left it to me. But I redid it, added onto it, I remodeled it. |

The Second Nazarine Baptist Church, founded in 1883

Penny: [the Nazarene Church] was on a plantation called Stanton Plantation, and before it came to Boyd Street was it on the plantation called Stanton. And then when Stanton had a flood in 1925, they relocated, and the Second Nazarene was rebuilt here. Before it became Boyd Street it was Common Street, when they moved from Stanton Plantation they brought it over here and rebuilt. And this church had like, I think, only four pastors. Rev. January, Rev. Moses, Rev. Crawford, and Rev. King. This church also had four pastors. Like the erection they did at Second Baptist, all the names that’s on the stone. |

The neighborhood cemetery

Dari: So, the thing about the cemetery is there's a lot of people that want to be buried there, or have wanted to get buried there, but they stopped allowing people to get buried there. Penny: Remember when Alvin was talking about the different societies? This is what he was talking about, the gravesites. Different parts of the gravesite; one part is for Eureka, one part is for Nazarene, and one part is for the Friends of Charity. And if you're part of Friends of Charity you buried in that spot, like this spot. Penny: This was a house too, this was a house and they tore it down and my cousin from California he bought this lot. But the people that own the society now, they was trying to purchase it this lot from my cousin so they can have more gravesites because they're running out of graves. That's why they really had to stop trying to bury people and have people go get their own policy to go somewhere else because they was out of space, because three different societies were owning this. So, if I'm part of Friends of Charity they won’t have no room to bury me because all the grave spots are taken, so what they would have to do is bury a person on top of another person. Penny: This grave right here. This is my aunt and my uncle. And see, she died first, so both of them was part of the same society, so when he died, what they did was put him on top of her. That they can have space for the next person whom you have pass that’s in that society. So, you’ll see a good bit of them with two names on their tomb. I don't know which part is Nazarene, was part is Friends of Charity, and what part is Eureka, so like I said, I was young when they started this, but I do know they're broken up into sections. Penny: This gravesite right here with these three little children, they had died in a house fire. And Mr. Lee where we’re going to make our last stop, that's his mama. That’s his mama’s grave. That's my cousin, when her children had gotten killed in a fire in 85’, they buried them all three together. The caskets were small; they were babies. So that's how they knew all three of them were able to get in that spot because they were real small. They were, one of them was a twin. So, they were like one-year-old and I think the oldest was like five. Q: How far back does your family tree go? Penny: About as far as I can get back from my family, for our people, is like from 1870. It’s hard to go back... Dari: It stops that slavery, pretty much. Penny: Yeah. So, it's hard. Some people like my cousin, she said she was able to get to the records, you know, get to the slave records too. Dari: I found some in South Carolina. Penny: You did? Dari: Well one side of my family, my sixth cousin…you know I did the swipe [DNA test]. Penny: You did? Dari: I've been connecting with people from all over. Penny: I don’t know why I haven’t done that yet. Dari: And we did six generations. And they were from South Carolina. |

![]()

Nola Sullen Rose: I’ve been down in this area all my life. I built this house about 50 something years ago. My in-laws, that house [pointing down the street], was my husband's parents’ home. His dad is 95 years old, but his daddy built another house about three streets over. His dad, there's a man that about 90 something, they have about four people in this neighborhood that's about 90 something years old, and basically the one that can give you more history about this area is Mr. Lee. History. He could tell you anything you want to know. His memory is just that good. And he's going on 95 years old. And there’s another one who lives over…he’s 94 or 96. Nola: One house over my grandmother used to live. She’s deceased, but she died at 99 years old. My husband's dad, he just got, he’s got Alzheimer’s now, but Mr. Lee, Mr. Gains, Mr. Davis their minds are sharp. They can tell you a lot of stuff about this community. It has changed a lot. It was…this community they called “the Cut Off” because it consisted of about three streets. The first street, which was named after my dad Sullen, because he did a lot of work in the community, to help get streets paved, and water, and all that stuff. This street, that street, and about four others. That was the whole community at one time. Since then it's just been expanding whole lot. I basically don't know, we don’t know people anymore. We knew everybody in this area here. We didn't even lock our doors. Everybody knew each other, walking in and out of each other’s homes and everything. But it has really changed a lot, not since Katrina, but before Katrina it changed a whole lot. That house right there [pointing next-door], I was a little girl when that house was put here. it's been here for, oh I don't know how long, a long time. Long time. Nola: When I was young there weren’t a lot of television. there weren’t a lot of cars. The older people basically took care of everybody. It was like one big family. If I did something wrong and the neighbor wanted to spank me or punish me, it was fine with my parents and everything. We didn't have a problem with kids that they have today. Kids weren’t disrespectful. We respected everybody because we knew if we say something and that person run up and go and tell our parents, we get spanked for it or punished for it. Not this generation. You can’t hardly tell them anything, you know. So, it's a big difference from when I was growing up. The way the children are raised, and the way now they call the police on their parents if the parents try to chastise them. We didn’t do those kind of things. We played. We had our little fights but never with weapons or nothing like that. And everybody stuck together. We helped each other. When I had something, my neighbor had it. Anything we had we shared with each other. That’s the way we grew up. |

Penny: We saw Alvin Rose earlier at Second Baptist and he was telling him about the different societies that we have here. So, he was asking Alvin, what are the different societies. We had Eureka, Friends of Charity, and Nazarene. So, he wanted to know what was the purpose of all these different societies. Nola Sullen Rose: The societies, they were means where people paid a certain amount of a month, and it was to keep up the graveyard, so if somebody died you automatically had a spot to bury. The graveyard still down there. There was two graveyards. And it also helped pay when people didn't have money to the doctor, it helped pay part of the doctor bills. And the doctor would come out to the home, we didn't have to go to the doctor, the doctor would come the house and see you. That’s why they had the societies: to help when people needed burial and all that. But now everything, you know, burial now is in the hundreds and thousands to get a burial spot. But they paid like $12 a month and that covered them going to the doctor and being buried if someone died. Q: Do these do the societies still exist? Nola: One of them do. One of them do, the Eureka they still have. The other two, they don't have them anymore. And they had a hall, each one of them had a hall where they would meet. There was one hall there [pointing] and they had another on the corner [pointing]. |

Penny: What do you remember about Rev. Reason Boyd? Nola: I was pretty young with Reason Boyd. I remember him being in that house on the corner and that he was blind and he would say, “hey!” [mimics a friendly wave]. And he used to, when they had baptism, they used to baptize out in the river, and he was blind, but everybody in the community would walk down the levee and go out into the river. And that’s where the baptism was done with Rev. Reason Boyd. They started baptizing at the church when Rev. Earl Green took over but I wasn’t one to go in the river. I was a little bit too young for that. Dari: But they still do the walk in the church as if they're going to the river. Nola: Yeah. They sing a song when they have a baptism in our church. They sing a song and they go, “we-are-go-ing to-the-streets of-the-city” and they’d walk all around as if they're going to the river. And when that happened everybody used to come out, just to see a baptism. During those days they got baptize in the river. I wouldn't get in the river now with all those oil boats. But we had to fear, nobody drowned! Q: When you say you didn’t do it, it that because they stopped it before it got to you? Nola: Yeah. By the time I got in church, they had built the pool in the church and they stopped doing that. But with Rev. Reason Boyd, that’s the only baptism that I ever remember him doing, was outside, marching to the river and baptizing in the river. I saw a lot of them. And after the baptism they’d go to somebody's house and have a lot of food. Penny: My grandmother, my great-grandmother, Eliza, that I was telling you about, she used to fix a big pot of gumbo after the baptism and everybody would go over to her house and eat. Nola: Eat, eat, eat, and enjoy the baptism. Penny: Like she said, it was just family here. You didn't really know who was kin and who—cause everybody was so close. |

He says the secret to a long, happy marriage is that he always gets the last word.

Well, two words: "Yes dear."

Q: What does it feel like now in the neighborhood? Nola Sullen Rose: The neighborhood now? I don’t feel as safe as I used to be. Because most the people that lived here are deceased, maybe a few of them that are still, and since they built all those different subdivisions down further, because like I said this was about five streets in the community, it’s just bad. When my husband is out there most the time and I say, “put the garage down because you don't who could walk in their while you out there!” Because I don't know none of these people anymore. I knew everybody that walked up and down the street. I don't know nobody anymore. It’s a whole different generation. And a lot of people migrated here after Hurricane Katrina. That's when it really got bad. A lot of those people who lost their home, they moved into some of the empty houses and apartments. And that's who really hangs in this area, not people we knew anymore. We don’t know everybody, we knew everybody at one time in this community. Totally different now, so it's not as safe as it used to be. And it could be worse, but it's just not a safe. You don’t know everybody. |

![]()

Penny: See this open Street? True story, our house was on this street. As kids they said to us, “your mama's house was on this street.” I grew up on this street as a little girl and I didn't know our houses was on this street until, when they cut a road open, and I said, “that looks like our house that used to be sitting there” but they tore it off. But this house was sitting there for years, we used to live right next door to this house here. But our house when we were growing up was right the middle of this street. And I wish I could have had a picture of it today. It used to be my great-grandmother's house, it was a double, so when we moved and ‘68 my great uncle, his family still was here. |

![]()

Mr. Lee, age 95, served in the Navy in World War II

Mr. Lee: You should’ve notified when you was coming, I would've baked a cake! [laughter] Mr. Lee: I was born in the Lower 9th Ward. I didn't move to the community until I was a man, in my teenage years. I enjoyed it. I was born on a plantation. Stanton Plantation, it’s below the intracoastal canal. It consisted of 80 or 90 families. It was called Stanton Plantation. I was born in 1921 there, then moved to Royal Garden, and from Royal Garden to the Cut Off. Penny: During that time did they have any midwives around here? Mr. Lee: The women having children, they didn't have no money to pay a doctor. The community, when the mother births the child, they had what they called the midwife. And that’s who, you know, assists the mother in the birth of the child. People didn’t have the money to afford a doctor. And they had two black doctors in New Orleans. And those were the only doctors we had. The black people didn't have no white doctors at all, except Dr. Larocca, his house was there in Algiers… Mr. Lee: And we had the navy base, during the war I went in—World War II—we had the navy base. Q: Were you in the Navy? Mr. Lee: Yeah, four years, nine months, and 37 days! Dari: You were counting down? [laughs] Mr. Lee: Yeah. I served four years in the Navy. I was drafted. They draft for no less than two years, but I enlisted for four years. I was there four years. And I worked myself up to a point six in the navy. The Navy had three branches: the messman branch, the seamen, branch and the officer branch. Negros belonged to messman branch. The white sailors had… fewer Negros going to the seamen’s branch. But the majority was in the messman branch and the officer’s branch. Mr. Lee: I was discharged in Tokyo, Japan in 1946. On the 12th of September the Japanese had just surrendered, and that's my military life for four years. I served on a destroyer and a PC, patrol craft. Most of my time I was on a patrol craft, PC, and later on I was on a destroyer, a destroyer 45. And I was discharged, when my eligibility came up I was 500 miles from Tokyo. And the captain told me, he used to call me smiley, “Smiley, you're eligible for discharge!” [chuckles] And he said, “I’m going to ship you over for four more years!” And I said, “oh, no! no! I said, “I want to get to a little village they call the Cut Off and I left a beautiful girl there, and I wants to go home!” He wanted me to stay for four more years. I was a cook in the Navy. I was a cook for the crew. I cooked for all of us. |

Mr. Lee retired as a carpenter and brick layer, and built many of the houses in Cut Off

Penny: Mr. Lee, so what was life like in the Cut Off growing up with Pastor Green and Pastor Reason Boyd? Mr. Lee: The Cut Off is the oldest subdivision in the state of Louisiana. And the reason why they call it “the Cut Off”: shortcut to Belle Chasse. They called it the Cut Off and changed the name from Southern Place. This was the only street in Behrman Highway to get the Belle Chasse. And around the river road, the gravel railroad, they had to go all the way around for 10 miles to get to Belle Chasse. The Cut Off was a brilliant place to live. People, they loved one another and they cared for one another, and they was poor. If you wanted sugar, run out of sugar, and your neighbor had sugar, and you send out for a cup sugar they’d send a cup of sugar. The neighbors provided for one another. Penny: When he came to the Cut Off there was no paved street, there was no plumbing. Mr. Lee: No paved streets, they had gravel. One road. The children had to put galoshes on, or boots on, to walk to school through the mud. Streets were mud and eventually they black topped the Street, and in some of these 20 years they had a young man by the name of Herbert Sullen. He got with the city and paid to black topped the street and a paved sidewalk from the river all the way to the school. All under the administration of the leader we had in this community, his name was Herbert Sullen. When all the children from New Orleans went to school, they couldn't walk with shoes. They had to have boots. there was mud when it rained. And they put the boots on out on the railroad and they walked with the railroad. When they got to the school they pull the boots off and put on their regular shoes. I remember that, during school. I was doing school at that time. |

With his grandson, an LSU student

Mr. Lee: I went to school at Booker T. Washington Trade School, in high school. I decided I didn't want to handle this stuff all my life. And I still took up my schools at Booker T. Washington Trade School in New Orleans. Q: What trade did you learn? Mr. Lee: construction, brick masonry, and carpentry. And I got my diplomas. Four years and each semester I did two diplomas. Dari: When was that? Mr. Lee: 1947. After I got out of the service. And the government created a bill for the veterans, the bill was four years free schooling and the government paid for it, and that's how I finished my education. Now I finished elementary education, and high school education. They didn't want to mix races. And Sister Josephine was the leader of Xavier University; broke that barrier. She was a nun and created Xavier University. Q: So, when did Xavier start? After the war? Mr. Lee: Xavier started long before the war. When I was a boy around 17, 18 years old. But they catered to light-skinned people. Dark skinned people like me couldn’t go to Xavier. Dari: Brown paper bag. Mr. Lee: And we had a school in Algiers called 35— Dari: McDonogh 35 Mr. Lee: 35 McDonogh, McDonogh 35. That’s right. I went to 35 and finished at Dillard. I got my, what would you call the degree…a teaching degree from Dillard University. Mr. Lee: I couldn't go to school when I was young, but on the G.I. Bill? Under the government’s G.I. Bill? My mama didn’t have no money to send for street car rides and bus drives to Dillard. It would cost twenty cents a day and she couldn't afford that. I was the eighth child. My daddy was pretty old when he married my mother. On the G.I. Bill I finished all these courses; I majored in construction. |

Three generations

Mr. Lee: I mostly worked around here, New Orleans, and Algiers. That where I stated. I built houses in Algiers, I built houses in New Orleans, and I built a number of houses in the Cut Off. Because I graduated in construction. I decided I was not going to use no shovels in the rest of my life! Penny: He was also a Sunday school teacher and a deacon at the church that we was at earlier. And he was a superintendent at the church— Mr. Lee: Later on… I was married at 21 years old. And I was so good in education, secondary education, that the church made me the leader of “The Teachers of Young People,” Sunday school they call it, bible school. A whole lot of people called it bible school. And Earl Green, or Reason Boyd was the second pastor of Second Baptist made me controller of the Sunday school department. When I was young I was determined I was going to advance more than my father. My father, he had no more than a fourth grade education, and I said, “oh no, that ain't good for me. I want to go all the way” [chuckles]. Eight children in the house; all the boys in one bed and all the girls in one bed [chuckles]. We was poor. Dari: Was your father was born on Stanton too? Mr. Lee: My father, a little bit on the side of Baton Rouge. And my mother was born north of Baton Rouge. And people come used to come to the city getting a job cutting cane down there. And that’s how my dad said that's how he met my mother. My mother was from some city in Louisiana…around the Mississippi River…but my mother was from some part of Louisiana, I forgot. In my daddy was a plantation farmer at Stanton. Dari: What did that look like? What is a plantation farmer? Mr. Lee: Plant sugarcane— Dari: Sharecropper? Mr. Lee: Sharecropper? No. Dari: Was he a…domestic worker? Mr. Lee: He was working. Dari: For free? Mr. Lee: No! It was nearly free. Two dollars a day or a dollar a day. My daddy really did earn three dollars week. |

A carpenter's hands

Penny: Tell them about the baptism in the river. Mr. Lee: They opened the doors of the church. All sinners, we Christians, we called them sinners. The invitation. They extended the invitation to all boys and girls and men and women to come practice Christ. The preacher had that prayer in his service that called sinners unto repentance and they call you up and you tell them what they believe in, “I believe in God, the father, the son, and the Holy Spirit and I know Lord according to my sins.” And they take you at your word and baptize you. Penny: Someone told me that before you got baptized you had to see something. You had to say you seen something. Mr. Lee: A travel. Penny: A “travel,” it was called travel. Mr. Lee: I had a travel. My travel was in the dream. I dreamed I was in water that high [holding his hand up to his chest] in the middle of the Mississippi River. I never forget my travel. And then I was baptized and I woke up. That was my travel. Penny: So, before he got baptized he had to tell the pastor, even though he saw that in a dream, he to say that before he got baptized. They would walk this whole street all the way up to the Mississippi River. And that's when they would get baptized. Now we’re in the church, but before they used to walk this same street before it got paved. Mr. Lee: Walk to the levy. Penny: All the way to the levy. Mr. Lee: Walk up to Norman, walk down to get baptized. And before that you to cross the levy into the river bank and baptize you over on the edges. Usually the water was that deep [holding arm to waist]. They couldn’t go no further. They called “stepping off”, no bottom. People got down. So that’s how I was baptized in the Mississippi river. |

Penny: And these are some houses on the left. People, they passed away. Either they passed away before Katrina, or after Katrina, but most likely they passed. And they just left their houses. This one was a house it got torn down because it was so old. And this was a house, I think the couple, they died and they just left the house, and that's why you see so much grass right there. |

![]()

Clarence "Frogman" Henry strikes a classic pose.

Mr. Henry had national hits in the 1950s and 60s,

and opened for the Beatles on their first American tour.

Clarence Henry: I’ve worked with a lot of musicians. I was 19, well I was 17 years old with Bo Diddley and Howlin’ Wolf in here New Orleans, but Ray Charles when I was 19. Jimmy Reed. Chuck Berry, that was my buddy! Etta James, you know, The Shirelles, Brenda Lee, Fabian, I mean a lot of these old time singers, I played with all of them. Ruth Brown , Laverne Baker, Lewis Lymon, Clyde McPhatter, Brooklyn Paramount with the this guy—Reet Petite, he would come on the stage with a cigarette. I don't know why, but he took ill and he was ill for a long time, you know. And I worked him. Jackie Wilson, I worked with him. Elton John. And Jimmy Buffett, he was crazy about me. A lot of these guys you see on the wall, Percy Sledge, and Charles Brown, and Little Richard [laughs] yeah, Little Richard. And a lot of these guys on the wall, Barbara from Beaumont, Texas; The Coasters; Jesse Belvin, and Jerry Butler, I mean—you name it. Johnny Preston, and Jerry Lee Lewis, and a bunch of them, Ike Turner, Elvis Costello. When I first went to England, they had Danny Williams, Helen Shapiro, and I think Tom Jones or somebody. They didn't have that many entertainers. Then I worked with Dusty Springfield, but they most of it was a lot of us, you know. And Sam & Dave, I did a session over there with Sam & Dave. Now, my dad was a musician, but never took a lesson. He could play any kind of stringed instrument, harmonica, and piano. Yeah, that man, my daddy would lay down there and at night, all the lights are out, had his wine—a gallon of vino muscatel, or even latter years with whiskey—and all the light’d be out, and my mama laying right beside me, and he’s singing his old blues like these old guys. Yeah, my daddy was musician. But he wasn't no pro. You know, he was entertaining, like if you came here he would play for you. And we had to get up, me and my brother had to get up to entertain people. At six o'clock in the morning my uncles would bring their girlfriends and we had that play for them. My daddy played like guys way back in the 30’s and the 20’s, you know, like then. Like Howlin’ Wolf, that stuff Howlin’ Wolf and them played, my dad played that. |

With his great granddaughter

Clarence: Mostly, we was born across the river, in the city of New Orleans. On Canal and Liberty, I was born, but I remember the Seventh Ward, where the St. Bernard ramp comes down off interstate, we lived there. In 1947 in the rent went up. And my first school was at Valena C. Jones and where we played at was called The Christian School, and the first movie was the Circus Theater. We had a good relationship in the Seventh Ward with the people around there and then the rent up in 1947. My daddy was paying $12 a month and it went up to $33 and he was going to pay it but they guy, the house because it was over a ballroom, you know. So, we moved over here on the West Bank, which is New Orleans, but they call it Algiers. My daddy rented a house, it was given to Dari, what happened was, we stayed there may be about two years or so, and my daddy bought a piece of property and his cousin who lived next door to him built the house. Dari: Mr. Lee. Clarence: Mr. Lee, Edward Lee. Mr. Lee charged my daddy to build the house $450, to build a whole house. It was two bedrooms, a living room, a kitchen. And we couldn't say bad because we had outside toilets then, and water, we had water then, but when we first moved to the Cut Off we had to go by my aunt’s and get water from her faucet, you know. I went to school down in Rodamore for half a year. |

In front of the Frogman's house, in a nearby Westbank neighborhood

Dari: So, what was the Cut Off like during that time? Clarence: When my mama moved and daddy moved to the Cut Off, you know, the people down there they was…. you know, the people— Dari: [laughs] Clarence: Her grandpa [pointing to Dari] was like the mayor, or the bigshot. The other people was nobody. They couldn't speak too good, “on-don-git-cha,” and things like that. The principle of L.B. Landry High School used to call us savages [laughs]. But in the Cut Off everybody was family. Everybody loved each other, I mean if you was mad with this guy, Christmas time you went to this house. There wasn’t no madness or nothing. No fighting, No killing. We didn't see any killing or nothing. No stealing. People used to leave their house, everybody had the same key, call a skeleton key, they would leave their door open and go in the city of New Orleans, come back and nobody steal anything, you know. And then one thing they had, if he had five brothers or three brothers, if fight him you had to fight all three of them. But the Cut Off, still it was family, everything like that. I was baptized when I was 15 years old at Second Baptist Church. Then my mama and my daddy, I had a good relationship with my parents. And my sisters and brothers we was together, because my parents was real strict parents. My daddy would say if you didn't go to school you had to work, there was no hanging around or nothing like that. He taught us not to be in a bad crowd, we didn't steal, we didn't smoke. My sisters and brothers and I, we was real tight. I had four sisters and one brother and we was real right. Her grandpa [points to Dari] was the mayor. In other words, the big shots were the preacher, her grandpa, and a couple other guys. But the other people was little bitty people down there [chuckles], but we all got along, that's why they named the street after her grandpa, Sullen. We used to call them “lane,” you know, the first lane, the third lane, and all that. The second lane, that was the preacher, the old-time preacher, Rev. Boyd. Now that's the one who baptized me. Rev. Boyd, he was blind, but he was great. |

![]()

Note. These photo portraits cannot represent the whole range of views in a neighborhood. My survey research tries to do that (see my home page). But I think that these photo portraits express views that are widespread in a neighborhood. This is due to the methodology. Qualitative work like these photo pages has more depth, while quantitative work like surveys has more breadth. Both are valuable, and if you want to know more about a neighborhood, you should try to learn about both. |

![]()

All materials which I created, including animations,

are Copyright © 1998-2017 by Frederick Weil; all rights reserved.

Main page: www.rickweil.com